In recent weeks, I came across three essays dealing with the outlook for continued scientific leadership by the United States. An op-ed piece in the April 17 Wall Street Journal by David Baltimore and Ahmed Zewail, both Nobel laureates and professors at Caltech, is pessimistic: “America cannot simply assume its lead in science will continue. In recent years the science community has been starved of the resources it needs. Young, new, energetic scientists are the seed corn of nearly all new scientific development. However, our schools, laboratories and granting agencies all, in one way or another, discourage launching a career in the sciences.

“The National Academy of Sciences issued a report, ‘Rising Above the Gathering Storm,’ that helped drive Congress to pass legislation – the American Competitiveness Initiative – aimed at bolstering the sciences. It was supposed to beef up the study of science in high school. In the end, no money was found to fund the initiative. It was a commitment made, but not kept.

“Our presidential hopefuls should be telling us their positions on critical science issues, but they have not done so yet.”

Reinforcing this view is the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, which issued a report in April bemoaning the state of innovation in America today. Among the specific challenges the report cited were increasing global competition, a slippage in American innovation leadership, innovation inefficiencies in private markets, and no national innovation policy.

But for at least one person, the glass is half full. Fareed Zakaria has just published a new book, “The Post-American World.” Zakaria, editor of Newsweek International and a keen observer of world geopolitics, is more optimistic. “Indeed, higher education is the United States’ best industry. In no other field is the United States’ advantage so overwhelming… with seven or eight of the world’s top 10 universities.”

So we have two pessimists and one optimist. What should we conclude about the future of science and innovation in the United States? Clearly, it is science that drives innovation, and innovation that drives America’s economic growth and ultimately determines its living standards.

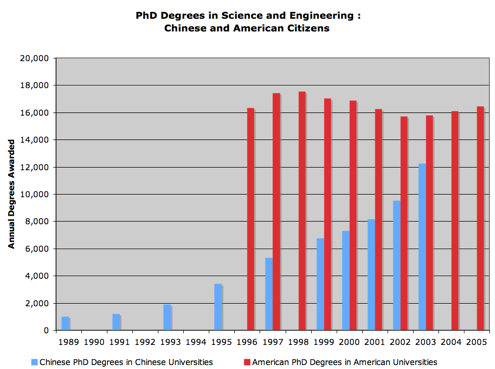

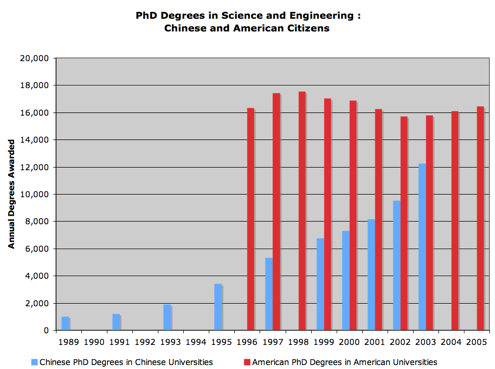

To get an answer to this question, let’s look at the data. One way of measuring the state of our scientific hegemony is to look at the number of Ph.D. degrees in science and engineering that our universities produce each year, and compare those with our newest and biggest competitor, China. As the chart below shows, as of 2003 we were still well ahead -- about 16,000 U.S. citizens received Ph.D.s from U.S. universities versus 12,000 Chinese citizens from Chinese universities. What’s ominous is the rapid growth of Chinese Ph.D. degrees in Chinese universities (the blue bars). Because of the rapid growth of Chinese degrees, I suspect that they’re ahead of us by now.

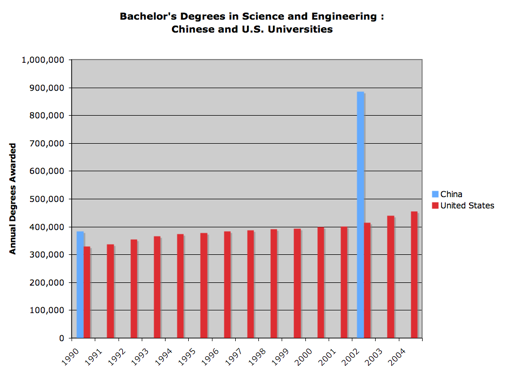

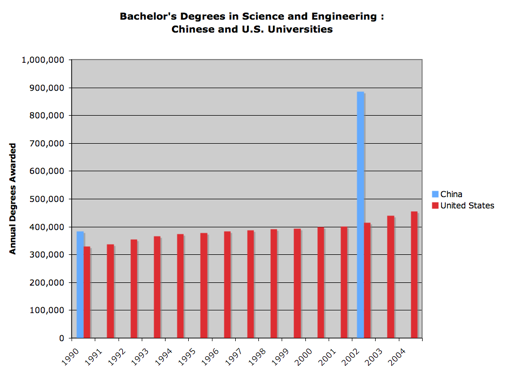

Another measure is the number of bachelor’s degrees in science and engineering from Chinese and American universities. In the last decade the number of Chinese BS degrees has almost doubled those of the US. It is probably true, as Zakaria points out in his book, the way that the Chinese define bachelors degrees is less rigorous than our definition -- they include many who have engaged more in vocational studies than in true four-year university engineering degrees. But however you define them, their numbers are growing rapidly while ours are increasing only modestly.

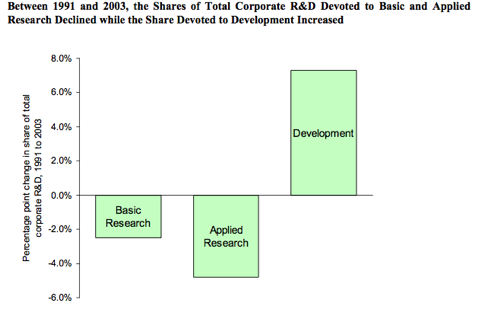

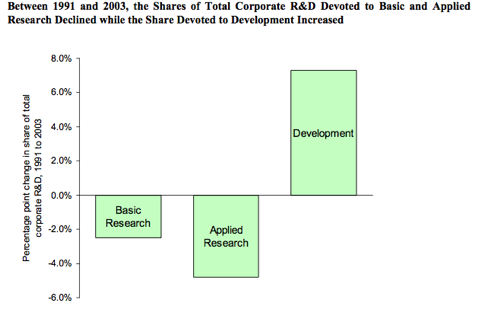

There is another measure -- the changing priorities in American industrial research and development. During the period from 1991-2003, corporate R&D shifted radically to favor development over basic and applied research. Development is growing at the expense of research, which is declining. In an earlier day, American industry supported some of the great basic and applied research laboratories in the world – Bell Telephone Laboratories, David Sarnoff Laboratory at RCA, General Electric and IBM research laboratories, and many other smaller but very productive centers of basic and applied research.

That has all changed. The emphasis in industry in recent decades has been to develop immediate commercial products rather than to win Nobel prizes for science. But because basic and applied research are the progenitors of subsequent development and innovation, we’re losing a great source of international competitiveness. Indeed, virtually all basic research today is funded by the federal government, with the majority of it coming from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation, both of which have been under severe funding pressure in recent years. In real dollars, NIH funding has been declining.

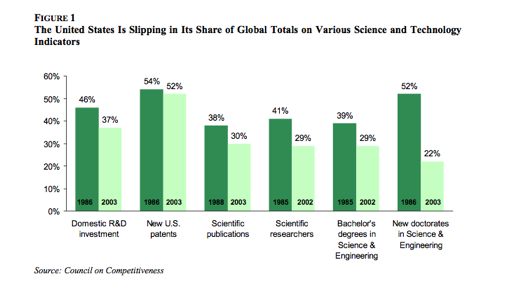

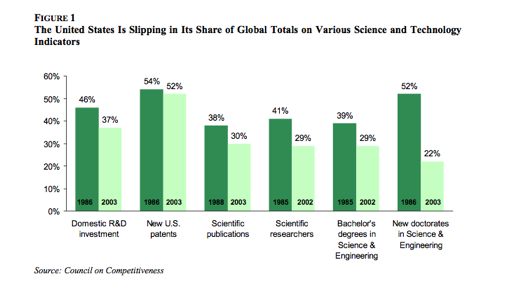

This final chart reinforces how our global competitiveness is slipping. Using six different measures, the Council on Competitiveness demonstrates how in the last 15 years the US has been losing ground to its international competitors in these drivers of innovation. Perhaps the most dramatic decline is in the number of new American doctorates in science and engineering (right-most bars), which has declined from 52% of the world total to 22%.

So despite Fareed Zakaria’s optimism about the future of American science and engineering education, it’s clear to me that we are slipping competitively. Basic and applied research are funded almost entirely by the federal government, and the federal government is showing diminishing interest in supporting what is the basis of subsequent innovation. Unless this policy changes with the next administration, it will have a deleterious effect on the American standard of living.

As Baltimore and Zewail point out in their essay, the lack of interest in science is shared by the political candidates of both parties – it’s an equal opportunity tragedy. Neither has said a word on science during the campaign. And it’s true that while science has few votes, it has big implications for our future.

Perhaps we need a wake-up call. In the last century the United States received two scientific wake-up calls that dramatically changed the way the nation looked at the need for science and engineering. World War II stimulated our scientific and technical output as no other development has before or since. And on October 4, 1957, when Sputnik was launched by the Soviet Union, it shocked the United States into a newfound – if short-lived -- interest in reinvigorating our scientific infrastructure.

It would be nice to believe that we could recognize our need today without the necessity of a shock or wake-up call, but it’s hard to be optimistic, particularly given the discouraging level of discourse at the political level. And though I like to look at the world through Rosen-colored glasses, my optimism is being severely tested.

“The National Academy of Sciences issued a report, ‘Rising Above the Gathering Storm,’ that helped drive Congress to pass legislation – the American Competitiveness Initiative – aimed at bolstering the sciences. It was supposed to beef up the study of science in high school. In the end, no money was found to fund the initiative. It was a commitment made, but not kept.

“Our presidential hopefuls should be telling us their positions on critical science issues, but they have not done so yet.”

Reinforcing this view is the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, which issued a report in April bemoaning the state of innovation in America today. Among the specific challenges the report cited were increasing global competition, a slippage in American innovation leadership, innovation inefficiencies in private markets, and no national innovation policy.

But for at least one person, the glass is half full. Fareed Zakaria has just published a new book, “The Post-American World.” Zakaria, editor of Newsweek International and a keen observer of world geopolitics, is more optimistic. “Indeed, higher education is the United States’ best industry. In no other field is the United States’ advantage so overwhelming… with seven or eight of the world’s top 10 universities.”

So we have two pessimists and one optimist. What should we conclude about the future of science and innovation in the United States? Clearly, it is science that drives innovation, and innovation that drives America’s economic growth and ultimately determines its living standards.

To get an answer to this question, let’s look at the data. One way of measuring the state of our scientific hegemony is to look at the number of Ph.D. degrees in science and engineering that our universities produce each year, and compare those with our newest and biggest competitor, China. As the chart below shows, as of 2003 we were still well ahead -- about 16,000 U.S. citizens received Ph.D.s from U.S. universities versus 12,000 Chinese citizens from Chinese universities. What’s ominous is the rapid growth of Chinese Ph.D. degrees in Chinese universities (the blue bars). Because of the rapid growth of Chinese degrees, I suspect that they’re ahead of us by now.

Another measure is the number of bachelor’s degrees in science and engineering from Chinese and American universities. In the last decade the number of Chinese BS degrees has almost doubled those of the US. It is probably true, as Zakaria points out in his book, the way that the Chinese define bachelors degrees is less rigorous than our definition -- they include many who have engaged more in vocational studies than in true four-year university engineering degrees. But however you define them, their numbers are growing rapidly while ours are increasing only modestly.

There is another measure -- the changing priorities in American industrial research and development. During the period from 1991-2003, corporate R&D shifted radically to favor development over basic and applied research. Development is growing at the expense of research, which is declining. In an earlier day, American industry supported some of the great basic and applied research laboratories in the world – Bell Telephone Laboratories, David Sarnoff Laboratory at RCA, General Electric and IBM research laboratories, and many other smaller but very productive centers of basic and applied research.

That has all changed. The emphasis in industry in recent decades has been to develop immediate commercial products rather than to win Nobel prizes for science. But because basic and applied research are the progenitors of subsequent development and innovation, we’re losing a great source of international competitiveness. Indeed, virtually all basic research today is funded by the federal government, with the majority of it coming from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation, both of which have been under severe funding pressure in recent years. In real dollars, NIH funding has been declining.

This final chart reinforces how our global competitiveness is slipping. Using six different measures, the Council on Competitiveness demonstrates how in the last 15 years the US has been losing ground to its international competitors in these drivers of innovation. Perhaps the most dramatic decline is in the number of new American doctorates in science and engineering (right-most bars), which has declined from 52% of the world total to 22%.

So despite Fareed Zakaria’s optimism about the future of American science and engineering education, it’s clear to me that we are slipping competitively. Basic and applied research are funded almost entirely by the federal government, and the federal government is showing diminishing interest in supporting what is the basis of subsequent innovation. Unless this policy changes with the next administration, it will have a deleterious effect on the American standard of living.

As Baltimore and Zewail point out in their essay, the lack of interest in science is shared by the political candidates of both parties – it’s an equal opportunity tragedy. Neither has said a word on science during the campaign. And it’s true that while science has few votes, it has big implications for our future.

Perhaps we need a wake-up call. In the last century the United States received two scientific wake-up calls that dramatically changed the way the nation looked at the need for science and engineering. World War II stimulated our scientific and technical output as no other development has before or since. And on October 4, 1957, when Sputnik was launched by the Soviet Union, it shocked the United States into a newfound – if short-lived -- interest in reinvigorating our scientific infrastructure.

It would be nice to believe that we could recognize our need today without the necessity of a shock or wake-up call, but it’s hard to be optimistic, particularly given the discouraging level of discourse at the political level. And though I like to look at the world through Rosen-colored glasses, my optimism is being severely tested.